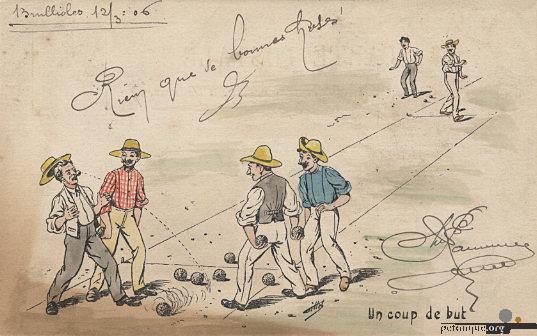

Games played with rolled or thrown balls date back to antiquity. We know that some form of ball game was played by the Egyptians, and then by the Greeks. The Romans learned it from the Greeks, and in turn taught it to the Gauls. In these games, the boule (bulla) was first made of stone. The Gauls, less skilled in stonework, made their boules out of boxwood (buxus), later known as bocco in the Provençal dialect, and bocce in Italian.st

Various forms of boules were played in the middle ages, and as the Gauls evolved into the French, boules continued to be played during the French Revolution and on into the 19th century. (The British played lawn bowls; the Italians played Bocce.) Regional forms of the game evolved, including “La Rafle”, “la Boule Lyonnaise”, and others. Rules were published, federations created and competitions started. Boules Lyonnaise became a recognized sport in 1850 with the creation of the first official club “Le Clos Jouve”. The Fédération Lyonnaise was created in 1906. It later evolved into the National Bowls Federation (1933) and then the French Boules Federation (1942).

Pétanque — a new variant of a very old game

Petanque was invented in 1910 [1] in Provence, in the town of La Ciotat, a small port town and island located on the Riviera coast between Marseilles and Toulon.

At that time thousands of workers were employed in the local shipyard, and their favorite entertainment was to go to a boulodrome on Sunday. The popular boules game was le jeu provençal, also known le trois pas (three steps) because (for many throws) players took a three-step run-up before launching their balls. The game was also known as la longue because the terrain was long — up to 20 meters. The terrain had to be long because it had to include room — on both ends — for the long pre-launch run-up. In some versions of the game, the two ends of of the terrain are marked off by lines. A player could run up to the line, but had to launch the ball before stepping across the line.

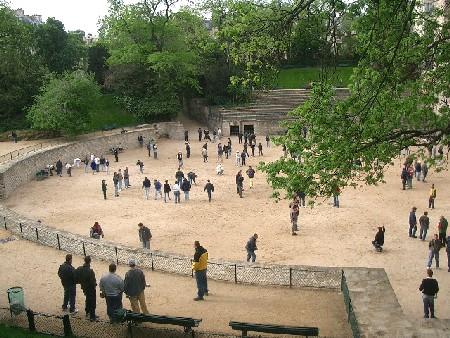

There were several boulodromes in La Ciotat and they were always full. The largest boulodrome was the Béraud, located near the Sainte-Croix cemetery. Nearby was La Boule Etoilée, a café run by the Pitiot brothers, Ernest and Joseph.

According to Ernest Pitiot, every day the best players of the region would meet — and play for money — with the shopkeepers of the town. The games attracted onlookers, and for a while the Pitiot brothers made a little money by renting chairs for 5 centimes to spectators who would sit “ring side” at the boulodrome, relax, watch, and bet on the play.

But this caused problems. Sometimes a shot boule would go into the crowd of onlookers. Spectators who were seated couldn’t get up and out of the way quickly enough to avoid interfering with the boules. The players (who, remember, were playing for money, and took the games seriously) were unhappy. In the end, the Pitiot brothers decided to stop renting chairs.[2]

The couloir of players and spectators probably looked something like this when the Pitiot brothers were renting chairs to spectators. (Photo by Robert Doisneau from the book “Les Boules” by Paul Garcin)

One of the seated spectators was a local shopkeeper (commerçant) named Jules Hugues, known to history as Jules le Noir (or Lenoir), after his nickname “le Noir” (Blackie). At one time he had been one of the local players, but he had become so crippled by “rheumatism” (arthritis?) that he could no longer play. In fact, he could barely stand.[3]

In light of his disability, Lenoir was allowed to keep his chair, but with the stipulation that he must sit near the circle that players drew on the ground to mark the spot where they could set down their boules when they weren’t playing.

And from there, our Jules who could no longer participate in any game, used to amuse himself shooting at 1.5 or 2 meters with the boules left in the circle. “I’m practicing” he used to say to me.

Lenoir was both a good customer and friend of Ernest Pitiot. So it’s not surprising that —

One day, certain of pleasing him, I offered to play with him, without moving, “feet planted” [pieds tanqués]…

It would have been natural, in that first-ever game of pieds tanqués, for Lenoir to throw from the chair where he was sitting, and for Ernest Pitiot to throw while standing next to him, in the circle. Martine Pilate, Ernest’s grand-daughter, says however that Lenoir insisted on standing, saying that “Boules is a game you play standing up.”

We started again the next day, and the following days. The old players, who numbered quite a few, watched how we played, well enough that my brother [Joseph Pitiot] organized a competition for the following Saturday. There were 8 teams of 2 players with a first prize of 10 francs.

Interest in the new game spread surprisingly quickly. As it spread, other rules of le jeu provençal were tweaked or dropped, making the new game even more attractive.

- The old jeu provençal requirement to “call the shot” (basically, to say in advance how you were going to throw the boule) was dropped. There was no longer any need to call the shot because all boules were thrown in the same way, while standing in the circle.

- The practice of routinely marking the positions of boules (so that displaced boules could be re-spotted if the player had called the shot incorrectly) was also dropped.

- Eliminating the need to call the shot and mark the balls greatly simplified the rules of the game.

- Because players no longer had to throw while running, it was easier to be accurate. The game became less difficult.

- With the running throw gone, the long run-up areas at the ends of the terrain could be eliminated, cutting in half the size of the terrain.

All of these changes made the new game not just different, but better — cheaper, less complicated, more accessible, more fun. Even its name became shorter and simpler. Jeu de boules pieds tanqués (game of boules with feet planted) quickly became simply pieds tanqués and then pétanque.

A new game was born.

Development of the all-metal boule

Two innovations created the game of petanque as we know it today — new rules, and a new kind of ball.

It is important to remember that in the early days, petanque, like its parent jeu provençal, was still played with the old nailed-wood balls, the boules cloutées. And in those early days, the production of boules cloutées was hampered by two things — a critical shortage of boxwood roots as raw material, and the First World War. The war ended and young men were able to return to their villages from the trenches. Many had suffered horrible wounds and lost arms and legs in the war. For them, perhaps, as for Jules Lenoir, petanque was a feasible game in the way that jeu provençal no longer was.

Then, between 1923 and 1925, petanque received a technological shot in the arm. In Lyon, Paul Courtieu developed a manufacturing process for the first hollow, all-metal petanque ball, la Boule Intégrale. Ironically, he did it by employing some of the technology for making hollow metal bombs and artillery shells that had been developed during the war. Because he was concerned that rust might be a problem, he avoided iron and steel, and made the first all-metal ball from a special bronze-aluminum alloy that he developed himself.

Then, between 1923 and 1925, petanque received a technological shot in the arm. In Lyon, Paul Courtieu developed a manufacturing process for the first hollow, all-metal petanque ball, la Boule Intégrale. Ironically, he did it by employing some of the technology for making hollow metal bombs and artillery shells that had been developed during the war. Because he was concerned that rust might be a problem, he avoided iron and steel, and made the first all-metal ball from a special bronze-aluminum alloy that he developed himself.

At its annual convention in January 1925, the Union Nationale des Fédérations de Boules approved la Boule Intégrale for use in official competitions.

Between 1927 and 1929, the first steel ball (remember, la Boule Intégrale was made of a bronze-aluminum alloy, not steel) was manufactured at Saint-Bonnet le Château, a small village located west of St Etienne, in the department of the Loire, Rhône-Alpes region of France. Courtieu had cast the entire boule in a single operation. Jean Blanc and Louis Tarchier, manufacturers in the village, developed a process in which steel blanks were stamped into hemispheres, and the hemispheres were then welded together to create the boule. (This process is used today for all petanque boules.) In 1928 Jean Blanc created the boules-manufacturing company that bore his initials— JB Petanque.

In 1904 Félix Rofritsch, a native of Alsace, settled in Marseilles and began making boules cloutées for jeu provençal. The company was successful, and when the new all-metal boules were introduced, Rofritsch bought a foundry and began producing all-metal boules. Félix’s two sons, Fortuné and Marcel, joined the company, and in 1947 they created the first boule made of carbon tempered Swedish steel. According to legend, heat treatment and hardening during the manufacturing process gave the new alloy a slightly blue color, so the Rofritsch company was renamed to La Boule Bleue. The Rofritsch family still owns the company and still manufactures La Boule Bleue; they are the only boule manufacturers in Marseilles.

Creation of the FIPJP

With the development of the steel boule, petanque began a meteoric rise in popularity. By 1935 there were an estimated 135,000 players in France, mostly in the South with a few in the Paris region.

During the 1930s and early 1940s, petanque was governed by the successor organization to the Union Nationale des Fédérations de Boules, the Fédération Française de Boules (FFB). The FFB governed several different types of boules games, but was dominated by the large number of boule lyonnaise players. Over time, a considerable amount of friction developed between the “traditionalists” and the growing number of petanque players.

In 1943, a big tournament was being planned for Montpellier. Ernest Pitiot, at that point director of the casino de Palavas-les-Flots, proposed that the competition also include pétanque. The story goes that the tournament organizers laughed him out of the meeting, calling petanque “un jeu de petite fille” — a game for little girls. Furious, Pitiot left, announcing that he would form his own federation for pétanque players. In a few days, the Languedoc-Roussillon league that he organized had 50 licensed players (licenciés, members), and it quickly grew to more than a thousand. The popularity of petanque was becoming impossible to ignore.

On January 16, 1945, representatives of boules committees from Basse-Alpes, Bouches du Rhône, Gard, Var and Vaucluse gathered in the O’Central bar in Marseille and founded the Fédération Française Bouliste du « Jeu Provençal et Pétanque », the FFBJPP. By the end of 1945 the FFBJPP had about 10,000 members.

The FFBJPP held its first championship tournament 1946, only a year after the end of the war. Before the competition began, the players marched to downtown Montpellier to lay a wreath at the war memorial. Martine Pilate, in researching her book about the brothers Pitiot, came to the conclusion that Montpellier, not La Ciotat, should really be considered the birthplace of petanque.

Ce qui m’a plus surprise fut de découvrir que, même si La Ciotat est le berceau de la pétanque, si Marseille revendique la pétanque, c’est en fait à Montpellier qu’elle fut officialisée pour la première fois.

What surprised me the most was the discovery that, even if La Ciotat is the birthplace of petanque, and Marseille lays claim to petanque, it was in fact in Montpellier that petanque was officially organized for the first time.

The popularity of petanque continued to spread, both within France and into other countries. A few years later petanque had clearly overtaken jeu provençal in popularity and the FFBJPP was renamed the Fédération Française de Pétanque et de Jeu Provençal, the FFPJP. For the first time, petanque got “first billing” in a federation name.

In late 1957, the Belgian Pétanque Federation organized an international tournament at Spa. At the tournament, players from six countries — Belgium, France, Monaco, Morocco, Switzerland and Tunisia — met and decided to create an international petanque federation. The six countries were later joined by a seventh, Spain, and on March 8th, 1958 in Marseille, the Fédération Internationale de Pétanque et Jeu Provençal, the FIPJP, was born. In the rules published by the new Federation in 1959, the old boules cloutées are finally forbidden and laid to rest.

In the the technological Stone Age before the World Wide Web, coordinating a multi-national committee was difficult, and the FIPJP struggled. Between 1959 and 1966, it managed to organize six world championship tournaments (Spa, Cannes, Casablanca, Geneva, Madrid, Palma de Majorca), but there were managerial problems. The first president resigned in 1961. The French Federation was having its own problems and withdrew from the FIPJP in 1964. No world championship was organized for 1967, and at the end of 1967 the second president resigned. By 1968, the picture was bleak. The International Federation was comatose if not dead, and the French Federation was sickly.

Fortunately, the French were able to rally themselves. In 1969 the FFPJP elected a vigorous new leadership committee. The new president, Mr. Paul, contacted the other national federations with a view to breathing new life into the FIPJP. There was a meeting in Marseille in 1970. In 1971 a world championship — organized by Henri Bernard, the young new General Secretary of the FFPJP — was held in Nice. At the FIPJP meeting in Nice, Paul and Bernard (respectively, the president and the General Secretary of the French Federation) were elected as, respectively, the president and the General Secretary of the International Federation. In 1977 Paul stepped down from the presidency of both the FFPJP and the FIPJP, and Henri Bernard was elected as the President of the FIPJP, a post he occupied for over 30 years. And there have been FIPJP world championships every year since 1971, without interruption.

The rise of Obut

In 1955, Obut, a new boules manufacturer, was established in the same small town, Saint-Bonnet-le Chateau, where JB Petanque was located. Frédéric Bayet, a lock manufacturer in St-Bonnet le Château, created the “OBUT” trademark. New fully automatic production machines were designed by Antoine Depuy, a talented mechanic.

In 1958 Bayet called upon the Souvignet family to help expand the production, and in 1981, Robert Souvignet became Chairman and Managing Director of Obut. Today his son Pierre directs the company.

Due largely to the efficiency of its automated manufacturing techniques, OBUT quickly grew to be the largest manufacturer of competition petanque boules. In the process, it drove out of business (or bought and discontinued) many smaller and older manufacturers, including JB Petanque and Elté, the two oldest manufacturers of steel boules. In 2013, after several decades of economic decline, La Boule Intégrale, the third of the three companies that pioneered the development of all-metal boules, finally closed its doors.

Today Obut has about an 80% market share for competition petanque boules. It employs about 130 workers, and manufactures over four million petanque boules a year. Its only serious competitors are Chinese manufacturers, which dominate the world market for inexpensive leisure boules, and Thai manufacturers (like La Franc) which make less-expensive competition-quality boules.

Recent developments

Since the very beginning, the FIPJP world championships had been bi-annual affairs (in even-numbered years) of men’s triples.

- In 1987, the FIPJP began holding bi-annual world championships for women (femmes), and for junior players (enfants).

- In 2015, the FIPJP began holding a men’s singles world championship.

In July 2007, La Ciotat held a celebration on the (supposed) centennial of the invention of petanque. The older gentleman in the gray vest and white hair is Jules le Noir.

In 2008, the world pétanque tournament, La Marseillaise, attracted 4,300 teams, almost 13,000 competitors and over 200,000 spectators from all over the world.

As of 2012, the FIPJP has 47 national federations as members and there are more than 600,000 licensed players world-wide. About half of them are located in France.

[1] It is sometimes said that petanque was invented in 1907, but that story seems apocryphal. All of the available evidence points to 1910. See our post on Ernest Pitiot and the birth of petanque.

[2] According to The Guardian, “This could cause problems, because people sitting near the jack were not above giving a boule a sly nudge with their feet every now and then, to push it closer or further away – whatever served a friend’s cause.” This doesn’t seem very plausible, despite the fact that The Guardian attributes the story to Martine Pilate.

[3] In more florid versions of the legend, Lenoir is a past champion and outstanding player of le jeu provençal, now tragically paralyzed from the waist down and confined to a wheelchair.

Sources

- petanque.com

- http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/jul/28/france-boules-petanques-got-cool

- http://home.earthlink.net/~detroitpetanqueclub/information/history.pdf

- History of petanque at petanque.org

- FIPJP History

- Musée de la Boule

- Marseillais du Monde

- IBC Office Petanque

- La Boule Bleue

Martine Pilate, the granddaughter of Joseph Pitiot and the grand-niece of Ernest, has written a historical novel about the creation of petanque — it is called La Véritable Histoire de la Pétanque, la légende des frères Pitiot (2005). You can read an interesting interview with her HERE.

If you enjoyed this post, you might enjoy some of our other history posts.